In her debut book, In Exile: Rupture, Reunion, and My Grandmother’s Secret Life, Pakistani Canadian journalist Sadiya Ansari chronicles a years-long investigation into one big secret that has long haunted her family: Why did her daadi (grandmother) abandon her seven children to follow a man from Pakistan’s Karachi to a tiny village in Punjab?

For so many South Asian families, where so much hinges on “log kya kahenge” (What will people think?), it’s a rare and personal glimpse into the roles women play when they defy cultural expectations and write their own rules—for better or worse.

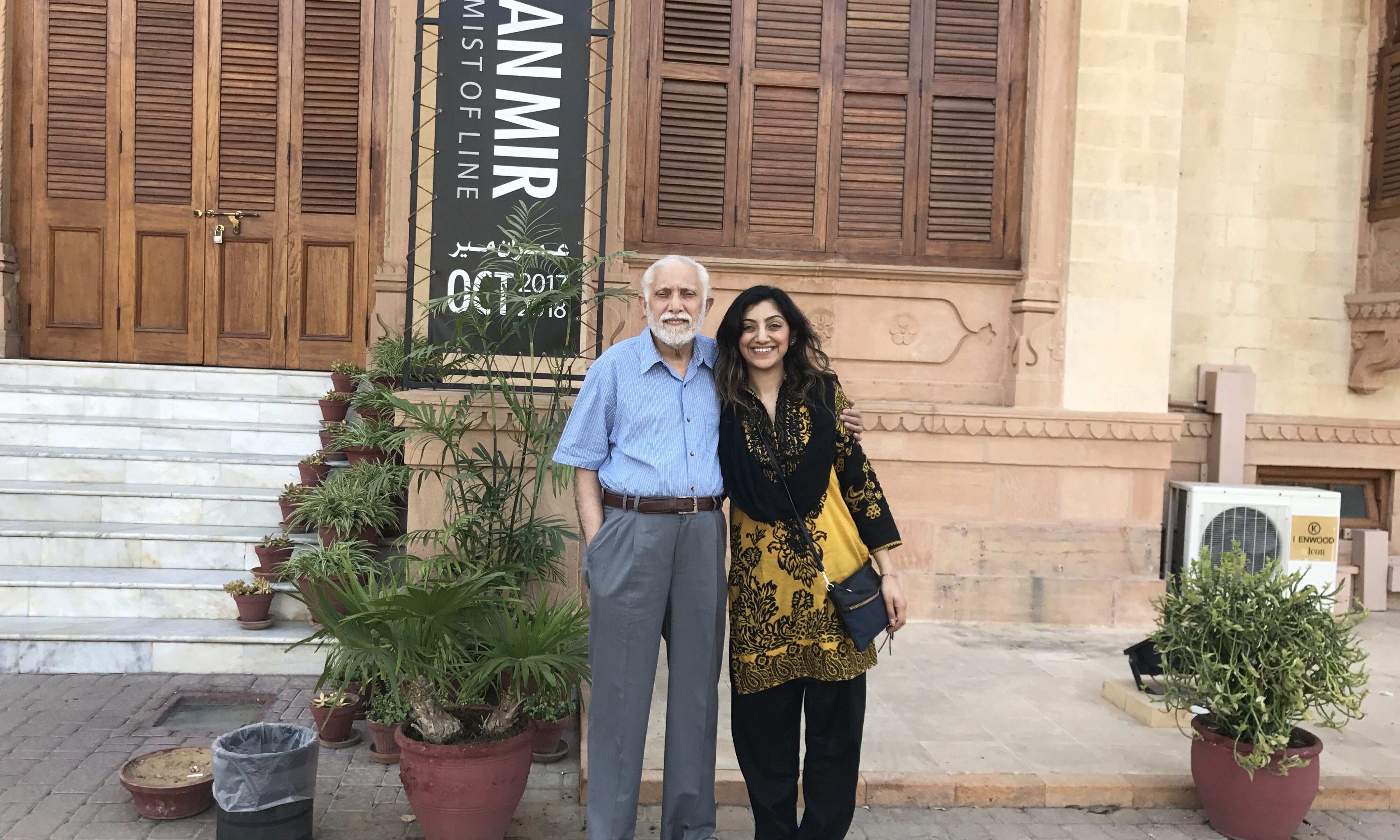

In her research, the London, U.K.-based Ansari travelled across three continents and interviewed countless family members—often alongside her father—finding belonging in a culture, in places and among people she didn’t quite expect to before.

Below, in an exclusive excerpt of the third chapter of In Exile, Ansari touches on this sentiment, and how home is more than just a place, but a feeling, too.

—

“They used to call him Paloo,” my dad told our surly Uber driver, as the rusted white minivan rattled over a bridge on one of Karachi’s ever-expanding roads. The story is a familiar one to me: my uncle allegedly played cricket with Pervez Musharraf, who later became Pakistan’s president through a military coup. While the tale was well-worn, this was the first time I was in that neighbourhood to see the pitch myself. The unending construction we drove by reminded my father of Paloo—he went on to try to school our driver in his own city, who remained surly but endured this. Musharraf was one of the only federal politicians who invested in the country’s largest city, my dad said, adding that before this bit of TLC, “it was an orphaned city.”

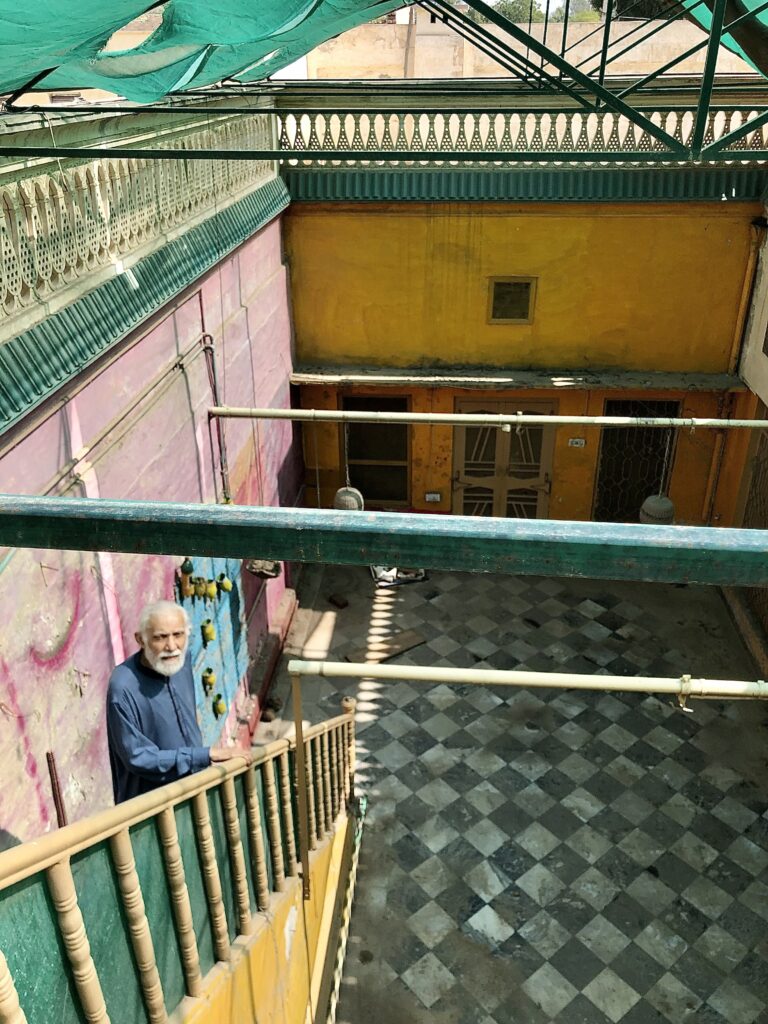

After barely being able to turn into a narrow street packed with cars and lined with litter, our driver slowed to a stop in front of an uninspired low-rise apartment building: 3F-10/4 in Nazimabad 3, an address my father and his siblings referred to simply as 3F. My father and I climbed out, stepping onto the dirt road. A woman peered over her balcony, perhaps suspiciously or perhaps genuinely curious why I was trailing a seventy-two-year-old, slow-walking man like a paparazzo, camera in one hand, audio recorder in the other.

The building stood where my father’s childhood home used to be. That home was one of many erected rapidly post-Partition, when Karachi’s population exploded from 430,000 in 1941 to more than one million just ten years later. This wasn’t the home he talked about fondly to me and my sister while we were growing up. He reserved that honour for Ehsan Manzil in Hyderabad. That was the home his father built for the family, where his siblings were homeschooled, where he chased rabbits. Not the two-room concrete structure his single mother moved them into after my grandfather’s death in 1956, where they lived a cramped existence, “just scraping by,” as he put it. And seven years after their father died, the seven siblings were left to take care of one another after their mother walked out of that home. That home in this orphaned city.

The sky became coated with that lovely early evening patina that makes up for the faint smell of sewage that hangs perennially in the city’s air, and we returned to our Uber, winding our way through chaotic traffic to settle in for the evening. Over tea, I made another attempt to broach the subject of what it was like to move to Pakistan, what life was like in that home. But he needed a break: “I don’t have too many happy memories.”

That was in 2018, my first trip back to Pakistan since I was ten years old. More than two decades had passed, and while I knew it was necessary, I was nervous about how my family would receive me as an unmarried woman who, in their eyes, was way past her prime. And, as a Pakistani Canadian, how Pakistani was I, really? I had pulled away from my culture and religion in my adulthood; neither seemed to have room for a woman like me. But upon arrival at Jinnah International Airport, I felt elated. The slight humidity of the early morning air not only felt familiar, it brought me a strange sense of comfort.

Something happens in the womb, or so a friend once told me, an attachment, an unexplainable environmental influence. Is this what led to my outsized affection for a city I was born but not raised in? The dusty roads at five in the morning were nearly empty. Streetlights were scattered and not all were lit. Dawn was still more than an hour away and the dried mud caked on the road seemed to reflect in the night sky. Dusty fragments of it whirled in the air, into the rusted white van my uncle was driving, falling in my hair, settling into my skin, and reminding me of the smell of home.

A few days after my father and I visited the site of his childhood home in Karachi, we headed to Lahore—the capital of Punjab, what people often refer to as the real seat of power in Pakistan.

The trip was meant to be part research, part sightseeing.

I wondered what I could find in provincial archives that might shed light on where Daadi lived or worked, and I also held out hope I could convince my dad to make a side trip to Haroonabad, the town my grandmother had disappeared into for fifteen years. Like Lahore, Haroonabad was in Punjab, and while it was hours away from the city, it was a lot closer than Toronto, or even Karachi for that matter. My father would get agitated every time I brought it up. He repeatedly told me there was no reason to go to Haroonabad: we didn’t know anyone there, no one who knew Daadi would likely be alive still, there would be no records in such a small town—his dedication to pessimism was almost impressive. I couldn’t even figure out how to prove him wrong. The logistics were a nightmare for some- one unfamiliar with the terrain: no hotels, a three-hour drive from the nearest city, and nobody I knew in Pakistan had ever heard of the place. I was out of my depth.

So I gave up on the idea and settled into the role of tourist, since Lahore has a much richer history than Karachi. Pre-British monuments dazzled me, even as they crumbled. The thousands of delicate mirrors adorning every surface at the Mughal-era palace Sheesh Mahal, the majesty in the tiles and engravings covering the ceilings of the Badshahi Masjid, and the serenity at Shalimar Bagh at sunset were a kind of beauty I hadn’t experienced before. I felt connected to it—it’s more likely my ancestors tilled land for the Mughals than hung out with them, but I still felt my heart bloom with pride in a way I’ve never felt looking at colonial artifacts in Canada.

We made one stop strictly for research: the Punjab archives, housed in a gorgeous white-domed building known as the Tomb of Anarkali. Popular lore says it was built for her by Mughal Emperor Jahangir—father of Shah Jahan, who commissioned the Taj Mahal—in 1615. Legend says Anarkali was in the harem of Jahangir’s father, Akbar, who caught her exchanging a smile with the prince and assumed a romance between them. Akbar had her buried alive between two walls, and later, Jahangir built the tomb to honour her. The British turned it into a church but kept her cenotaph there. Today, it houses the most complete archives in the subcontinent, dating back to the 1600s. As I went through photos, maps, arrest records of those who resisted the British, my insides wrenched realizing that these documents weren’t available to Indian scholars. As someone who grew up outside the subcontinent, it was the first time I realized how hardened the borders had become. And it made the couplet engraved into Anarkali’s marble resting place feel that much more apt: “Could I behold the face of my beloved once more / I would thank God until the day of resurrection.”

One of the only places Indians and Pakistanis converge en masse is at a daily flag-lowering ceremony at select border crossings, one of them at Wagah, thirty kilometres from Lahore. As my dad and I neared the border, we went through eight checkpoints. Our car was checked for bombs, the interior swept for weapons, our IDs examined. Past the final checkpoint, our driver dropped us off at a parking lot a few hundred metres from an imposing structure rising from the flat, dusty landscape: A stadium stood at the end of the Pakistani side of Grand Trunk Road, which, for many years, was the only road that crossed the border.

The crowd thickened as we drew closer to the stadium. The ceremony began an hour before sunset, and while time was a loose concept across the country, military time retained its meaning. The anticipation was palpable among the thousands gathering—twenty thousand in total showed up daily on both sides. My father, who had been reluctant to make the excursion, became enthralled with the spectacle around us. As we entered the grand gate, an arch of red brick flanked by two white columns, we spotted a man in full regalia—a lush black outfit lined with gold buttons, topped with a black turban with delicate gilded thread outlining each fold. My dad excitedly asked for a photo, and surprisingly, he obliged.

There was a section for locals and a section for foreigners in the open-air stadium. We were instructed by an usher to sit in the fourth row, which, like us, wasn’t quite in either category. The stands formed a semicircle around the performing space, which was cut in half by a wrought-iron gate, closed ahead of the show. On the other side of the gate was the Indian stadium. I had never been to a sports game with my dad but this pretty much felt like one, although absolute allegiance to a country rather than a team electrified the atmosphere. An aggressive hype man screamed into a microphone on a podium high above the crowd, beside a massive portrait of Pakistan’s founder, Quaid-e-Azam.

“Pakistan ka matlab kya?” he screeched.

“La ilaha illallah!” the crowded shouted back.

The Indian spectators had their own hype man, and I wondered how long the screeching could go on for when a trumpet silenced not only those on their mics but the entire crowd. A dhol player started up, signalling the beginning of a fascinating performance from each side. Then the gate between the two stadiums opened. Over the next thirty minutes, the dhol beat quickened while Indian soldiers and Pakistani rangers faced each other, thrusting their legs up as high as possible, landing dramatically closer to their opponent each time, and then, finally, meeting in the middle and lowering the flag for the evening.

Only a pandemic and a war have stopped this ceremony. It remains a sign of brotherly collaboration and friendly competition. But the nationalism, boosted by a healthy dose of testosterone, thrumming in the stadium terrified me. And both the earnestness and zealousness of repeating “Pakistan zindabad!” confused me.

When people ask me what my “background” is, I say Pakistani, but I clarify that both my parents’ families lived in India pre-Partition. My family’s history is rooted in both, and it always seemed strange to pretend they were such separate places, to root for one cricket team, to pledge loyalty with the severity it seems to require. While the increasing persecution of Muslims in India is doled out as proof that the creation of Pakistan was indeed necessary, the narrow idea of what kind of Muslim has become acceptable in Pakistan doesn’t support early ideas that this new country would protect religious freedom more effectively. The conflation of nationality and religious affiliation is of course intentional, but it erases the rich history that came before 1947. A history where religion wasn’t always at the centre of identity, one that I increasingly longed to understand.

Get the

Three from 3

newsletter

Join our global community of sharp, curious thinkers to receive a carefully curated email of the three most important things to read, see and do this week.

Listen and learn.

Tune into Third Culture Leaders, a podcast hosted by our co-founder and publisher, Muraly Srinarayanathas.

Explore how leaders skillfully navigate multiple cultural landscapes, leveraging their diverse backgrounds to drive innovation and change.

My family never talked about Partition, so I never considered it part of our story. Like most crucial, life-altering events, it simply remained an unpleasant chapter not worth discussing. As a result, I imagined Partition as I learned about it at school. I thought of it as a painful but singular event—like a blade to skin, blood rushing out, followed by healing. But the reality is much messier: an estimated one to two million dead, fifteen million displaced, entire communities destroyed, and religious divisions that have not only endured, but deepened.

My father was born just two years before the British withdrawal, but the violence was already intensifying. Witnessing one of the first major massacres in Calcutta in 1946, American photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White likened the scene to the Nazi death camp Buchenwald, which she had been at the year before. Pakistani American historian Ayesha Jalal, who has studied Partition over decades, didn’t mince words in a piece co-published by Dawn and the Hindustan Times: “Partition is undoubtedly one of the most momentous events in history, not only in terms of administrative dismantling, but it also resulted in large scale displacements and the mass killings of people,” she wrote. “We cannot minimize Partition’s legacy.”

The mass disruption, migration, and violence didn’t all happen in 1947 when the British conveniently and cowardly fled. Over the four years that followed Partition, nearly fifteen million people moved, and that movement continued into the 1950s. The borders in the early days were permeable, as were people’s identities. As the writer Saadat Hasan Manto put it: “Despite trying, I could not separate India from Pakistan, and Pakistan from India.” He was staunchly committed to staying in India, but even he was so shaken by the violence he saw post-Independence that he ultimately left for Pakistan.

This new separation, no matter how arbitrary it felt, upended millions of lives, including members of my family. For Daadi, staying in India until the mid-1950s meant being without her parents and most of her extended family after they fled for Pakistan, leaving her without a lap to lay her head on in her loneliest hour, after her husband died. And that meant she too had to leave the only country she had ever known, the only place she thought she’d ever live.

- What is the meaning of Pakistan? There is no God but God! (This exchange references the first kalima, which recognizes there is one God and Muhammad was his last Prophet.)

- Long live Pakistan.