Atiba Hutchinson is runway ready. He’s wearing a COS knit golf shirt and short set that seem tailored to highlight his calf muscles, still lean and taut with tensile strength even 11 months into his retirement. Add the black socks and black-and-white wing tips, and Hutchinson, a Canadian soccer legend, looks as fresh and sharp as the location for this photo shoot—a brand-new fenced-in, turf-surfaced soccer pitch on Vodden Drive in central Brampton, Ont., that bears his name.

If the 41-year-old Hutchinson were strutting along a Parisian boulevard during Fashion Month, those wing tips would make his outfit pop. But for now they’re inconvenient. The photographer needs him to do keep-ups with a soccer ball, but those kicks are made for fashion, not footie.

You try to let your kids know where they’re from. Not just Canada. Denmark. Trinidad. What helped was seeing me play for Canada.

“It’s impossible with these shoes,” he says.

But Hutchinson is an expert in achieving the improbable.

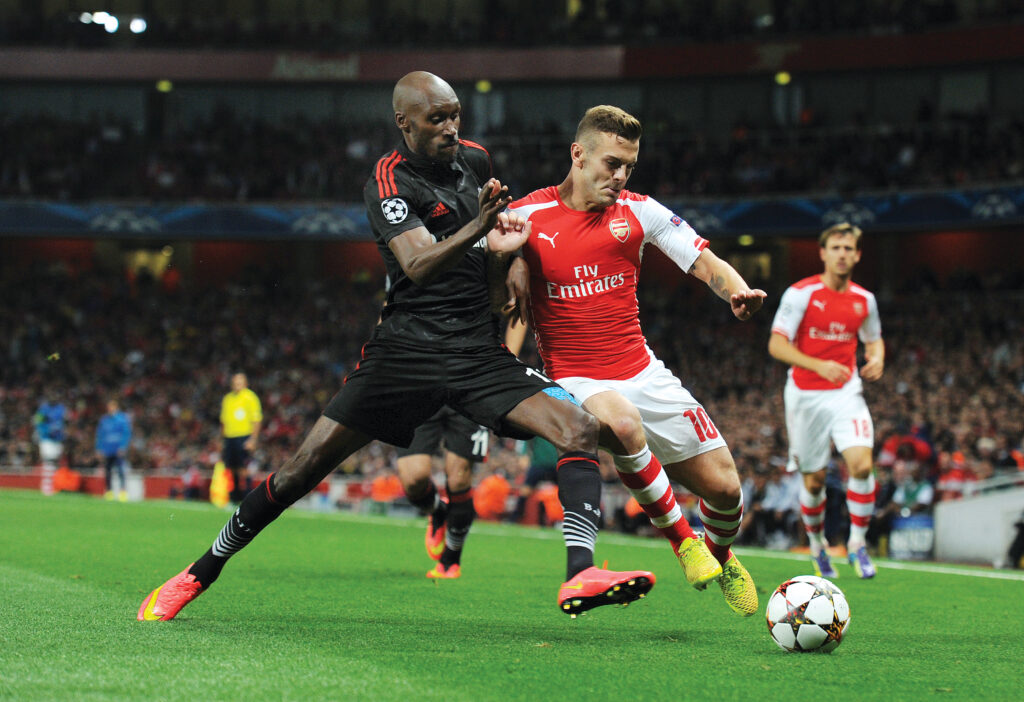

The Atiba Hutchinson Soccer Court, a five-minute drive from his childhood home, is Brampton’s tribute to his legacy and his 21-year professional career. Hutchinson played in the UEFA Champions League with FC Copenhagen, and in the 2022 World Cup with Team Canada. He hasn’t just shared the field with some of the world’s top soccer players. He’s been one of them.

In 2002, when Hutchinson first joined the York Region Shooters of the now-defunct Canadian Professional Soccer League, there was no clear path to the top for this middle child of Trinidadian immigrants. He forged his own through perseverance, attention to his craft and a willingness to travel nearly anywhere for a tryout. His resumé includes short stints in Sweden and Italy, longer ones in Denmark and Holland, and an 11-year run in Turkey, where he still lives.

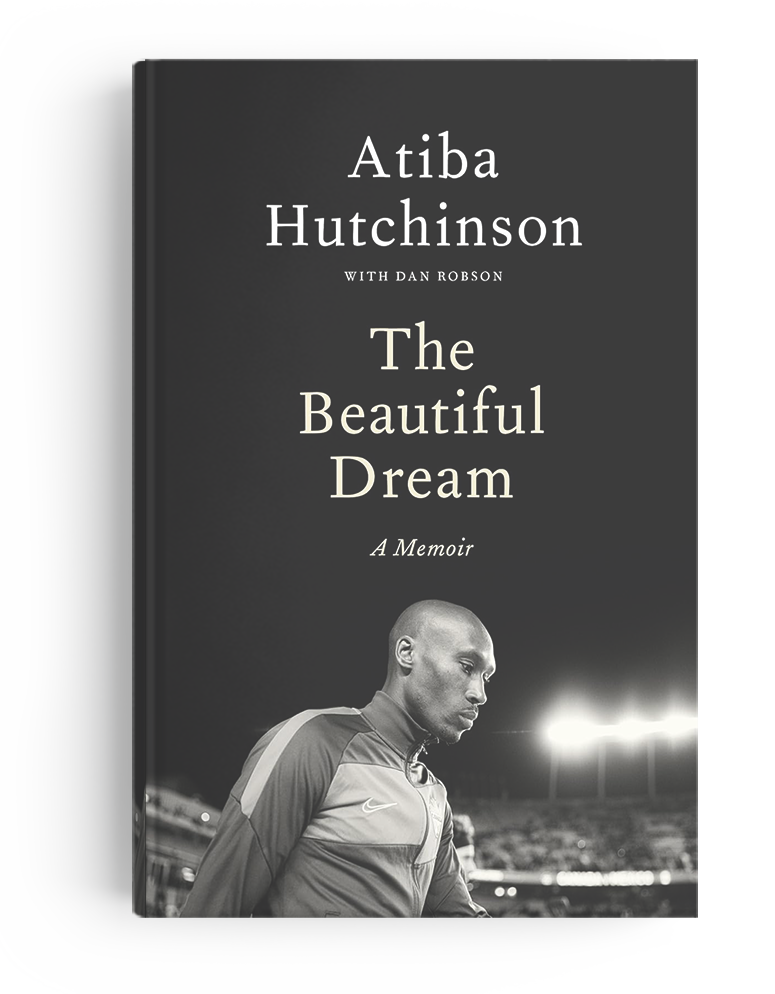

He details his journey in his new memoir The Beautiful Dream, co-authored by veteran sports writer Dan Robson. As he fiddles with the intricacies of doing keep-ups in wing tips, he explains why he always returns to his roots.

“More than half my life I’ve been in Europe, but home is always going to be Brampton,” says Hutchinson, who graduated from Notre Dame Catholic Secondary School. “You can’t really go away from the good times you’ve had.”

In his book, Hutchinson zooms in on a crucial goal FC Copenhagen made in the Champions League against Manchester United, the powerhouse English club. Hutchinson didn’t score—his header set up a teammate for the finish—but the play electrified him nonetheless.

“It was a dream,” he said. “The stadium was on fire when we scored that goal.”

It’s also his broader career in microcosm.

On that play, Hutchinson connected the free kick and the big goal. On the Canadian national team, he bridged the frustration of the program’s past and the optimism that defines its present. Hutchinson joined the senior national team in 2003. He became a central figure on those late 2000s teams that never equalled the sum of their parts, failing to qualify for the 2010 and 2014 World Cups, even with standouts like Dwayne De Rosario and Julian de Guzman. Hutchinson remembers that time as a string of lacklustre results, and home fixtures that felt like away games. In August 2008, Team Canada took the field in Toronto and played Jamaica to a 1–1 draw as fans cheered and banged drums and waved flags…for the visiting team. It was normal back then, when Team Canada often underperformed, and local fans with roots in other countries hedged their bets.

“It was always a frustrating thing to see,” he says. “Where are the Canadians?”

Except, Hutchinson understands; he cheered for Trinidad and Tobago as a kid. His parents passed down one nationality; he grew up with another. Like many first-generation Canadians, he made room for both—and now, so do his four kids. Hutchinson’s wife, Sarah, was born in Denmark to Persian parents. Their children were all born in Turkey.

“You try to let them know where they’re from. Not just Canada. Denmark. Trinidad,” he says. “What helped them was seeing me play for Canada. They feel really Canadian.”

This conversation is taking place a short drive from the Brampton duplex where Hutchinson grew up, but arriving here required a slightly longer drive—plus a 10-hour flight from his current home in Istanbul.

A day into his first visit to the Turkish capital, in 2013, Hutchinson didn’t necessarily envision himself staying there. A short stay in a bug-infested room in a shoddy hostel shortly after he and Sarah arrived almost soured him on the idea of Istanbul.

But Hutchinson explored the city on the not-so-remote chance that his soccer career might take him there next. At 30, he had just finished a successful three-year stint with PSV Eindhoven in Holland, and entered free agency hoping he could land a spot in the English Premier League, or Germany’s Bundesliga. But he had also played alongside several players who had spent time in Turkey’s Super League, and had urged him to explore the opportunity if it ever arose. Even if the salary couldn’t match what players made in the EPL, the passion of local fans was unmatched.

In the summer of 2013, Hutchinson received a contract offer from Beşiktaş, a powerhouse of a club with 16 Turkish Super League titles to its credit and a passionate fan base supporting it. He accepted, understanding that as a 30-year-old pro athlete, any new contract might be his last.

From a soccer standpoint, it turned out to be the right assignment at the ideal time.

Eleven years into his pro career, Hutchinson had accrued the soccer IQ to read plays before they developed, allowing him to save steps and make better decisions on offence and defence. But at 30, age and injuries hadn’t yet slowed him, and he could still make plays that required raw speed.

Over the next decade, Hutchinson would play 270 matches for Beşiktaş, scoring 24 goals and sprouting roots in his new hometown. He and Sarah enrolled in classes to learn Turkish. (She now speaks it more easily. He does not.) And he has stuck with the city through turbulent times. After an attempted coup in June 2016 rattled the country right down to its storied soccer league, several of Hutchinson’s teammates left Turkey for good. In his book, Hutchinson writes about grappling with fear and uncertainty that summer, and about opting to stay.

By then he knew two things about the concept of home: it’s where you’re from, but it’s also where you wind up, and choose to make yourself comfortable. So, as much as Brampton would always be home, Istanbul was too. It’s where he established himself as an all-time favourite with Beşiktaş, where he’s enjoying his post-retirement life, playing padel (a racquet sport that originated in Mexico) three times a week and where, since the birth of his first son, Noah, in April 2015, he has felt a natural attachment.

Curiosity is our engine.

Sign up to discover what we’re reading, seeing and thinking about each week.

Listen and learn.

Tune into Third Culture Leaders, a podcast hosted by our co-founder and publisher, Muraly Srinarayanathas.

Explore how leaders skillfully navigate multiple cultural landscapes, leveraging their diverse backgrounds to drive innovation and change.

“It was supposed to be another stop in this beautiful dream,” Hutchinson writes. “But standing there, holding baby Noah, surrounded by love, we knew this was the place where our greatest dreams would unfold.”

As for the keep-ups…they’re possible, even in polished wing tips. The photo session continues and here’s Hutchinson, controlling the ball as if it’s tethered to his feet, at home in Brampton, at home on the pitch.

“My mind was always, whatever it takes to get there is what I’m gonna do,” he says. “I never got discouraged. I just had to keep working.”

Dreaming of the beautiful game in a hockey-mad country

The patchy field behind Arnott Charlton was our Old Trafford, our Bernabéu—our very own field of dreams. It was where we practised what we’d witnessed on weekly satellite broadcasts of the Premier League or La Liga.

We divided ourselves along ethnic lines for the tournament. In Brampton, on its way to becoming one of the world’s most multicultural cities, it was never difficult to fill a squad. There were teams from Jamaica, Spain, Portugal, Ghana, among many others. Alex played for the Italians. I was a skinny, undersized striker for Trinidad.

Any kids without compatriots were placed in a hodgepodge group that reflected Canada itself. No one wore that title with pride. In our adolescent world, playing football for Canada carried little weight. We didn’t dream of wearing red and white, representing our nation against the world. There wasn’t enough inherent pride in the nation’s football history to warrant such a fantasy.

At that time, it was difficult to imagine something that we had such minimal exposure to. Some of us might have known about Canada’s 1986 appearance at the World Cup—the only time a Canadian team had ever appeared in the globe’s most revered tournament. But we were only toddlers when coach Tony Waiters had led a scrappy Canadian team through a historic qualifying round and earned a trip to Mexico to compete for international sport’s grandest prize. Canada had failed to qualify ever since, so competing for our own country was not something we dreamed about.

Across the country, hockey was still the sport of our national identity—the frozen game that Canadians had dominated for nearly a century. It was the sport Canada was famous for, our cultural touchstone in the world. We were the birthplace of Wayne Gretzky, king of the cold climate sport, which relatively few nations actually play. Hockey was a monochromatic sport, which—especially in the 1990s—made little room for newcomers. In other words, it was a sport for wealthy white kids. For the kids who were never asked where they were really from, because it was assumed that they were from here. But rapidly growing Brampton was a place where an increasing majority had deep cultural roots elsewhere. And so our passion was found both home and away, with a unique sense of identity rooted in both where we were now and where we had come from. And the sport of “elsewhere ”—the global game so many young people in the Toronto area inherited a love for from their parents who’d made Canada home—was football.

So within our group of friends competing to be champions of the world, we played proudly for the nations of our parents. This was the World Cup of Brampton’s own. It was as intense and serious as the actual World Cup could possibly be.

In one of the most memorable tournaments, Trinidad played Jamaica in the final. It was me, my cousin Kevin, and our friend Dwayne against a couple of our friends and this ringer they brought in, who was about five years older than the rest of us, basically a grown man. But we held on and won the World Cup for Trinidad. We celebrated as though we were actually hoisting that gold trophy, the most gorgeous prize in sport—two humans holding up the globe, like hands hoisting a football. We spent our winnings at the local Beckers convenience store like proper soccer stars, lavishly and irresponsibly on things we didn’t need, like sour keys, Oh Henry! bars, and sunflower seeds. When I lay in bed at night, my imagination carried me to only one beautiful dream. One day, I’d play in a real World Cup—as near impossible as that seemed.

Adapted from The Beautiful Dream by Atiba Hutchinson with Dan Robson. Copyright © 2024 Atiba Hutchinson. Published by Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.