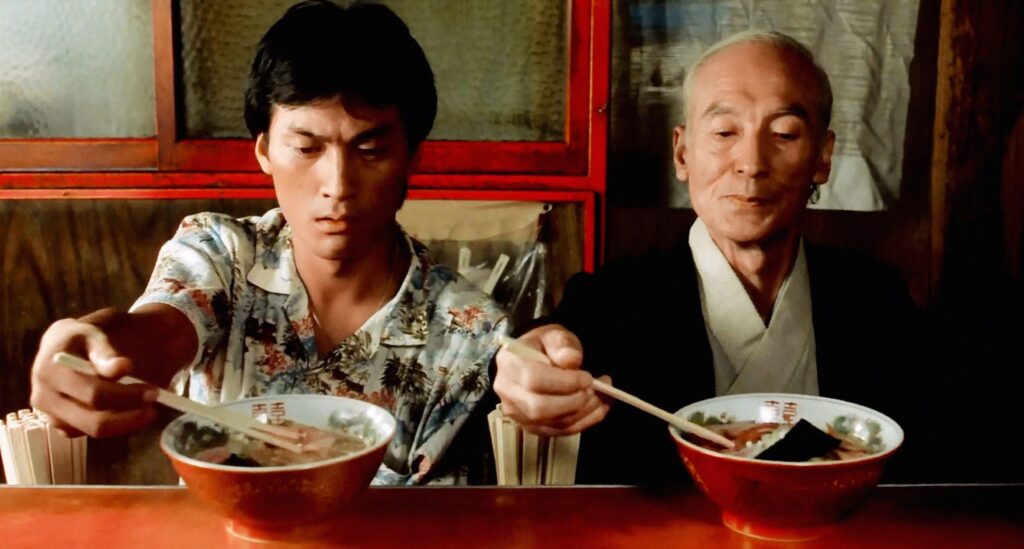

From the making of the restaurant-rescuing timpano in 1996’s Big Night to the egg yolk that gets passed between a yakuza gangster and his lover during a very open-mouthed make-out in 1985’s Tampopo, to the intricate and rhythmic opening cooking scene in 1994’s Eat Drink Man Woman, some of cinema’s most delicious and memorable scenes have revolved around food.

Of course, those scenes are rarely just about the dishes on the table. They’ve come to stand for much more, whether it be family, love, sex or just a hard conversation. That’s part of why the relationship between food and film is so meaningful—no matter the culture or cuisine, it’s an integrated and universal language. Naturally, then, it lends well not only to cooking your own Godfather-worthy tomato sauce or watching Marie Antoinette with friends while snacking on decadent macarons reminiscent of those in the French court, but also to larger-scale events and festivals that can bring a wider community and culture together.

That is the logic behind the growing phenomena of food-themed film fests across Canada and throughout the rest of the world. In fact, you’d be hard-pressed to find a major community without one. Asia has a number of them, including the Seoul International Food Film Festival, the Busan International Film Festival and the Tokyo International Film Festival; Europe has the Nordic FoodFilmFestival and the Italian Hungry Minds; Africa has the Nollywood in Diaspora Film & Food Festival; and the United States has the Fork n’ Film, among others.

“Foodways are a defining part of a culture and a significant aspect of identity,” says Emily J. H. Contois, associate professor of media studies at the University of Tulsa. “Many food films tell these stories. While not as wedded to ‘the truth’ as documentary film, narrative film tells food stories that can influence what we know about the world and our own place within it.”

Lia Rinaldo, managing director of Devour! The Food Film Fest, a Nova Scotia–based festival, agrees: “When we watch a film that showcases a dish or a dinner scene, it often evokes emotions and memories, creating a connection between the visual and the sensory. We often describe what we’re doing at Devour! as ‘tasting the screen.’ The films we tend to curate don’t just present food, they celebrate it as a central theme, revealing the essence of human experience—sharing meals, celebrating moments and telling stories. Food in film serves as both a narrative device and a cultural marker.”

This is why it’s also so easy to remember not only the specific dishes featured in some of these films from decades back, but also the particular lines that accompany them— case in point: When Harry Met Sally’s “I’ll have what she’s having.”

“These films and series encourage viewers to value culinary heritage, engage with food as a cultural experience and embrace cooking as both personal expression and social connection,” says José Eduardo Villalobos Graillet, a Spanish instructor at Wilfrid Laurier University and expert in Spanish film studies. “They turn recipes into living legacies, inspiring audiences to cook, explore and share stories through food.”

And that goes all around the world. For instance, in many of the East and South

Asian films that spotlight a family dinner

or cooking together in the kitchen, not a whole lot is said at the dinner table. That’s because, culturally, feeding each other is a conversation in itself—tantamount to saying “I love you.”

The commentary food in film provides can be more complex too. In the 2005 Iranian film The Fish Fall in Love, for example, the fish market symbolizes how society has changed over time, particularly in the challenges women face. Other times, it can be much simpler, like how 1997’s Soul Food reminds us that, literally and figuratively, one meal can be healing, and fried chicken or collard greens can be a simple lunch for one person but a feast of shared history for another. By passing those recipes and foods down through generations, family traditions are sustained and languages are preserved.

Social media is also a temple for the interplay between film and food. Take New York film critic and journalist Kristen Yoonsoo Kim (a.k.a. @meals.on.reels), whose name alone is inspired by David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. She uses her account to spotlight obscure and underrated cinematic food moments, like Shelley Duvall’s character’s love of tuna melts in 1977’s 3 Women, or the boycott around Sal’s Pizzeria in 1989’s Do the Right Thing. Then there’s @curmudgeonclay, who recreates popular film and television dishes, like Severance’s melon bar and waffle party or Inglourious Basterds’s apple strudel (with cream!). Today, countless other Instagram and TikTok accounts have caught on to the trend, spotlighting moments in food and film history from decades back and from more underrated international archives.

More than simply an ode to comestibles, these posts remind us why the practicalities in these movie moments are also so powerful. “Food in film renders every aspect of our food lives and systems as intimate and larger than life at the same time,” Contois says. Putting food at the centre of the story and our sensory experience as viewers, “it makes logical sense that those structural and stylistic choices make food delectable and uniquely thought-provoking for viewers.” And this can apply to everything from the mundane —like shopping for groceries — to the spectacular — like gorgeously plated dishes and colourful ingredients.

With close-up shots of a dripping chopped cheese or a greasy pizza slice or even the rings left behind from a “damn fine cup of coffee” (the infamous line uttered by Kyle MacLachlan’s character Special Agent Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks), you can almost taste or smell the dish onscreen.

“These visuals awaken memories and emotions linked to our past experiences, making food onscreen a powerful connector to our identity,” Graillet says. “It opens our appetite and draws us into the world of the kitchen, where culture and emotion blend seamlessly. Food becomes a character itself, carrying stories of tradition, family and belonging.”

Spanish cinema, in particular, excels here. Enriqueta Zafra, associate professor and chair of the department of languages, literatures and culture at Toronto Metropolitan University, cites a modern example: this year’s short film Debí Tirar Más Fotos, directed by musician Bad Bunny and filmmaker Ari Maniel Cruz Suárez.

Get the

Three from 3

newsletter

Join our global community of sharp, curious thinkers to receive a carefully curated email of the three most important things to read, see and do this week.

Listen and learn.

Tune into Third Culture Leaders, a podcast hosted by our co-founder and publisher, Muraly Srinarayanathas.

Explore how leaders skillfully navigate multiple cultural landscapes, leveraging their diverse backgrounds to drive innovation and change.

In the film, an older version of the musician reflects on his past and laments not having taken more photos and, therefore, having more memories to revisit. “But,” Zafra says, “memory finds its way back through food: a simple quesito (a sweet cheese pastry) becomes a representation of community. Returning to his neighbourhood café, now gentrified beyond recognition, the musician orders a quesito that—ironically—has no cheese. Everything has changed. Yet it’s in this moment of total disorientation that he quietly insists, ‘We are still here.’”

Zafra continues, “That phrase acts like a signal. The people who are still there respond: the cook knows the kind of cheese he is talking about, and a man at the bar pays for his snack in a now cashless café. It’s a tender reminder that while places may transform, shared memory, food and community can still offer a sense of home.” So much so that it went viral on social media, as many fans revisited the quesito, its cultural significance and differing family recipes. Sales of the pastry rose too.

Whether it’s a quick snack between work and errands, a languid brunch on the weekend or a wine-soaked mid-week dinner, the first way we take our food in is by sight. We make note of the enveloping steam, the plating, the way the Parmesan adds freckles to our rigatoni or the condensation drips down the side of our soda can, fresh out of the fridge on an especially hot summer day. Those visions are enough to provoke hunger and thirst. Imagine, then, the great privilege of getting to actually take a bite or a sip? And to be transported to a time, a place, even a person?

“From the sweetness of a quesito to the sensual absurdity of ham to the deceptive calm of chilled gazpacho, these films show that food onscreen isn’t just about appetite,” says Zafra. “It’s about identity, longing, memory and survival. To taste is to remember, to resist and to belong.”