Danzy Senna’s new novel, Colored Television, a struggling biracial novelist-turned-screenwriter begins working with a hotshot Black TV producer who establishes the stakes of the cultural landscape: “Diversity, diversity, diversity. The default is whiteness. They get this flurry of interest in us every few years, but if you don’t strike fast and hard, they return to the tundra. You know how it works.” Released in late 2024, the book arrives in the wake of box office hits like Jordan Peele’s Get Out, and Issa Rae’s critically acclaimed series Insecure. Senna satirizes the way identity politics has become cultural currency, literal cash, in America. Its nerviest passages brim with the energy of a collective knowing.

These days you can’t scroll Instagram, or TikTok, if you’re more vertigo-resistant—without encountering so-called ethnic comedy: usually young Americans, Canadians or Brits who are performing short bits riffing on racial or cultural stereotypes about their own communities.

Walpole Island TikToker Eagle Blackbird (@Itzeaglee) plays with tropes of an “Indigenous wisdom giver,” with long hair blowing in the wind and flute music playing in the background, cheekily sending up Hollywood-invented images of Native people, while also acknowledging Indigenous world views. In other videos, like those by British-Punjabi TikToker Aman, also known as the Gud Morning Pineapple guy (@aman100oktenkyou), the content is pure non sequitur and the accent—in his case, a kind of pitched-up, lisping mutation of an Indian cadence—is the joke.

And then there’s a more subtle kind of ethnic comedy, popularized by creators like Linda Dong, who goes by the moniker Leenda Dong to emphasize the accent in her comedy

(@yoleendadong). The Vancouver TikToker’s videos have become so ubiquitous on social media that even people who use Instagram only casually know her by face, if not name: she’s the frazzled-looking young Asian woman who always wears big glasses, a topknot and an oversized sweat suit. She has created sponsored posts, in character, for the NFL, Kia and more, including one for Prime Video featuring John Cena. Much of her recent content is silent, building humour through an exacting combination of facial expression, body language and a scenario-specific caption, but in earlier videos, Dong’s character spoke in a vaguely Chinese accent that, as it turns out, wasn’t actually hers.

Ethnic comedy emerged from American vaudeville, a form of theatre that captured the plight and sensibilities of a growing immigrant and multicultural working-class population. It took on a new sheen, modern but still self-deprecating, in the heyday of stand-up via comedians like Jerry Seinfeld, Ray Romano and Brampton’s Russell Peters. And over the last decade or so, through social media apps like Vine in the late aughts to TikTok today, everyday people, looking for representation and relatability, are building characters and personas around a form of comedy rooted in their ethnic or racial identities.

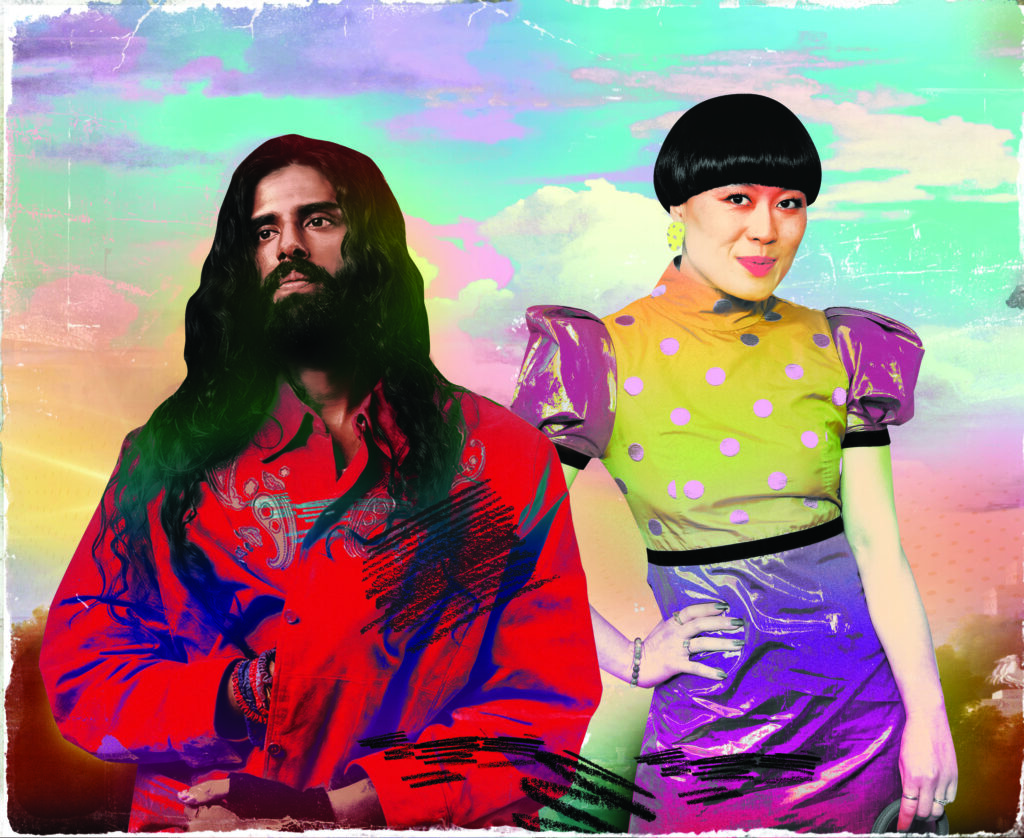

Neema Naz, a content creator and actor from Toronto, describes his comedy as “very based around ethnic jokes, about my own culture and others, and the intricacies between that and Canadian or American culture.” Naz reveres Russell Peters—he calls him “the OG”—who coined international punchlines from the hyper-specificity of a multi-ethnic upbringing in Brampton, and his Anglo-Indian ancestry. Naz’s family is from Iran and his feed includes short-form videos of him portraying various Persian characters, as well as clips from stand-up shows. Sometimes, but not always, an accent makes an appearance. “As a young kid I always had an innate ability to mimic my family’s accent and the accents of my friends’ parents, who were also immigrants,” says Naz. “I have friends from everywhere and I was always fascinated with culture. It shaped the person I am today.”

Naz is aware of making this kind of content in a climate where race and identity-based conflicts have become more polarizing and prominent. “Life is hard. It’s difficult and sad most of the time,” he says. “The older you get, you realize how much worse it is. There are people who see my stuff and think it’s ‘racist’ because they have a different lens than me. But comedians are on stage to make people laugh. Along the way you’re going to offend people, but they’re not trying to hurt people.”

Writer and comedian Fatuma Adar says she can’t do an impression of her Somali parents to save her life. “There is something beautiful to it. To be able to capture the cadence of your mother,” she says. “But the audience can’t tell if you’re doing that to get us closer to a story—or if the joke is the accent. How do you control what people are laughing at? You can’t.”

As a young person, watching comedians like Peters use different accents—Indian, Jamaican, Chinese—got her closer to a story that felt familiar. “He had this joke about a conversation between kids where the white kid goes, ‘When I do something bad, I get sent to my room,’ and the Brown kid goes, ‘You have a room?!’” She laughs. “It was like spilling secrets. Russell Peters had to walk so we could get a more nuanced portrayal of Brown comedy.”

In 2023, Adar mounted a musical comedy show, She’s Not Special, at the Tarragon Theatre in Toronto that drew on the experiences and pressures of being a Black Muslim artist. Adar says the jokes felt different to deliver depending on who was in the audience each night. “The comedic dynamic is about the relationship between the audience and who is on stage,” she says, adding that the audience is often the final component of developing the material. “All of a sudden a context is created, and that’s why stand-up is high-key, very scary.” You can hear this relational magic at play on the album version of She’s Not Special, which was recorded during a Black Out Night, a showing set aside for Black theatregoers.

Her favourite comics aren’t people who think, I don’t care who is in the room; I’m gonna bulldoze, but are the ones who are intentional about being present with their audiences. She pauses, wary, then adds: “This isn’t my pitch for crowd work.”

Adar is active on social media and she seeks out fellow Somali comedians, especially young women, who do bits about their families and the pressures of community, sometimes with accents; “it’s funny because their moms sound like my mom.” She says this is important, especially within a culture where speaking your mind, or speaking out of turn, is frowned upon. “There was an era of comedy where people were doing impressions of their parents. It was like, ‘Look how silly our jokes and customs are.’ [I] think of the white audience sitting before that.”

What’s changed is the room itself, and just like real life, sometimes we find ourselves in the wrong room online. Adar calls TikTok “the promoter from hell” for the way it constantly lobs new faces and personalities at users, subtly shaping the way we laugh. We are all looking at the same things, laughing constantly, for different reasons at different times. “If you’re a comedian using social media, you’re delivering to an audience of one, several millions of times—and if I, the audience of one, don’t laugh, then is something not funny?”

Writer and actor Bahia Watson first co-wrote Pomme Is French for Apple, with Liza Paul, and mounted it at the 2012 Toronto Fringe Festival. The show was a youthful West Indian mash-up of The Vagina Monologues, complete with pink stretchy fabrics and folk songs—and Caribbean accents. It ran for five years, including performances in Edinburgh and New York City. Since then, Watson has moved from Toronto to Los Angeles and has acted in popular series like The Expanse and The Handmaid’s Tale—but the biggest shift she’s noticed is that social media has created a more tangible connection to Caribbean creators. People living in the diaspora have a more direct relationship to that cultural experience.

Watson recently revisited the script and was satisfied with how it’s aged. “It’s really funny,” she says. “The butt of the joke is not the accent.” She grew up in a Guyanese household in Winnipeg, and says that, while writing Pomme, she was “enjoying the language, and the way the language has its own humour—not everything translates.” But recently, she’s become self-critical about performing with an accent.

It’s no longer central to her recent work, including Mashup Pon Di Road, a Caribbean feminist circus show, and Shaniqua in Abstraction, for which she received a 2024 Dora Award nomination. The feelings she’s wrestling with represent an artist who is, with courage and empathy, thinking deeply about the implications of their craft. “I don’t know if shame is the right landing place, but I am trying to negotiate respect. Being plugged into a lot of discourse can make you hyper aware and now I’m self-conscious, and there’s no one to ask because everyone has a different experience.”

Comedy is inherently disarming, says Watson. It can connect disparate ideas or formations, unearth new feelings and even make you want to cry. And it can go to these places, she says, “because you’re laughing, and that opens you up. You’re loose.” But she’s curious to understand how the desire for that opening, vulnerable as it might make a comedian, can also cause harm. “I’m not deeply invested in hard lines of censorship, especially at a time when people can choose what they want to support,” she says. “If there’s harm, is it more on the TikToker or is it on the audience that’s following them? Algorithms are designed to respond to what we’re responding to—it reflects something that’s present in our society, the good and the bad.”

A 2010 article republished in the Sociological Inquiry titled “The Impact of Comedy on Racial and Ethnic Discourse” highlights the way that humour captures communication—especially ideas and precepts that are in flux. “Joking about the hardships of minority status allows minorities to release social angst in a way that does not threaten the dominant group.” These jokes depict a society that only “appears more racially integrated than evidence otherwise suggests it is.” This sets up the paradox of ethnic comedy, which addresses, directly, racial differences and experiences of racism, but also uses logic of colour-blindness to appeal to wider audiences. Comedy is a tool of media and ideological dissemination. And for platforms that run on capitalist technology, like social media algorithms, this is a payload: more impressions, more data and more and more screen time from users.

So while ethnic comedy certainly stirs up feelings and associations—some good, some bad—it’s worth considering that we rarely encounter this work in a neutral way. And as Adar and Watson both point out, even the crowd in a theatre or bar is determined by demographic forces that can either invite or dissuade diverse audiences. Who runs the theatre? How much do their tickets cost? Is it a gender-inclusive space? These contexts inform the way we understand the potential of comedy to shape social relations.

For many, especially those who live and socialize within spaces that exist beyond the gaze of power centres, and oftentimes under its thumb, ethnic comedy has traditionally functioned as a stepping stone to broader recognition. It’s the specificity of life in diverse communities, “that’s what has made me and my friends laugh,” says Naz. Turning a local bit into a worldwide punchline can be transcendent in how it brings people together. And when it’s good, it has the power to endure beyond identity-based paradigms of relating. This is what Toronto’s Jasmeet Raina, creator of the beloved Vine character JusReign, is doing with his series Late Bloomer, which is currently in production on a second season. Unlike Vine, where Raina impersonated a mother figure, Late Bloomer offers a more fulsome portrayal of a Punjabi family. Played by first-time actor Sandeep Bali, the mother character has dreams and eccentricities that soften the roles and traditions of an immigrant household. And the new workplace comedy series The Office Movers by Brampton-raised brothers Jae and Trey Richards takes inspiration from their own father, who has a decades-old office moving business. The patois punchlines recall their pioneering YouTube shows, like Judge Tyco, but the context pays tribute to multi-ethnic blue collar workers who populate the Greater Toronto Area.

Get the

Three from 3

newsletter

Join our global community of sharp, curious thinkers to receive a carefully curated email of the three most important things to read, see and do this week.

Listen and learn.

Tune into Third Culture Leaders, a podcast hosted by our co-founder and publisher, Muraly Srinarayanathas.

Explore how leaders skillfully navigate multiple cultural landscapes, leveraging their diverse backgrounds to drive innovation and change.

However, their success won’t be determined via laugh meter, and viral success alone is an insufficient gauge for how audiences are responding to discernable tonal changes from a new comedic vanguard. Comedy can be a democratic artform, but it is also a product within a market fuelled by algorithmically derived targets carried out by a shrinking number of executives. Netflix Canada recently announced that it will scale back funding for training and development programs, delivered by organizations such as the Pacific Screenwriting Program and the imagineNative Institute. This is due to new Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) regulatory demands requiring companies to contribute five per cent of annual Canadian revenues back into various funds promoting domestic content. Social media content was once a direct-to-consumer intervention in the screen and entertainment industries, but now virality is looking more like a winning lottery ticket.

The audience can’t tell if the joke is the accent. How do you control what people laugh at? You can’t.

Fatuma adar

The stakes are higher, financially and politically. Though ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, doesn’t publicly disclose financial data, a Financial Times article from March 2024 reported that the app generates billions in sales. And that number is growing, despite the U.S. government’s attempts to force the Chinese company to sell to an approved buyer or be banned, like it was by the Modi government in India. On November 6, 2024, the government ordered TikTok to cease operations in Canada—without actually banning the app itself. The story is still developing at the time of print, but in addition to the geopolitical implications, this will presumably impact the income of the app’s most viral Canadian creators.

Making a living in comedy requires alchemy to achieve sustained success—determining how to tell jokes on your own terms while also locating the sweet spot of wide appeal. In Senna’s book, the novelist-turned-screenwriter is moving through a world that churns on this logic—that race, whether it’s Blackness or whiteness, or biracial-ness, is a commodity that can be exploited. To make that choice, or not, can significantly alter your material reality. It’s a premise that works because it drives at the heart of the current political moment, pointing directly at the ways in which our ambivalent and always-evolving internal feelings about identity are up against ROI. That is to say, it’s funny because it’s true.