Emblazoned on the walls of Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), unforgettable lyrics by rapper Cardi B speak to hip-hop culture’s unapologetic bravado: “Now I like dollars/I like diamonds/I like stunting/I like shining.” This refrain, from her 2018 single “I Like It,” introduces gallery-goers to an exploration of the custom of adornment in hip-hop culture—one of the six thematic pillars in a new exhibit, running at the gallery until April and entitled The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

In the 50 years since hip-hop was born in the Bronx neighbourhood of New York City, the musical style has evolved into a way of life, complete with its own musical canon, aesthetic trends, styles of dance, fine art and spiritual principles. True fans are always ready and willing to debate the top five greatest emcees of all time, and even those who don’t care for the genre can probably define and understand its nuanced lingo. Hip-hop today, as the exhibit aptly lays out, is much more than just music. It’s a wellspring of contemporary art and influence.

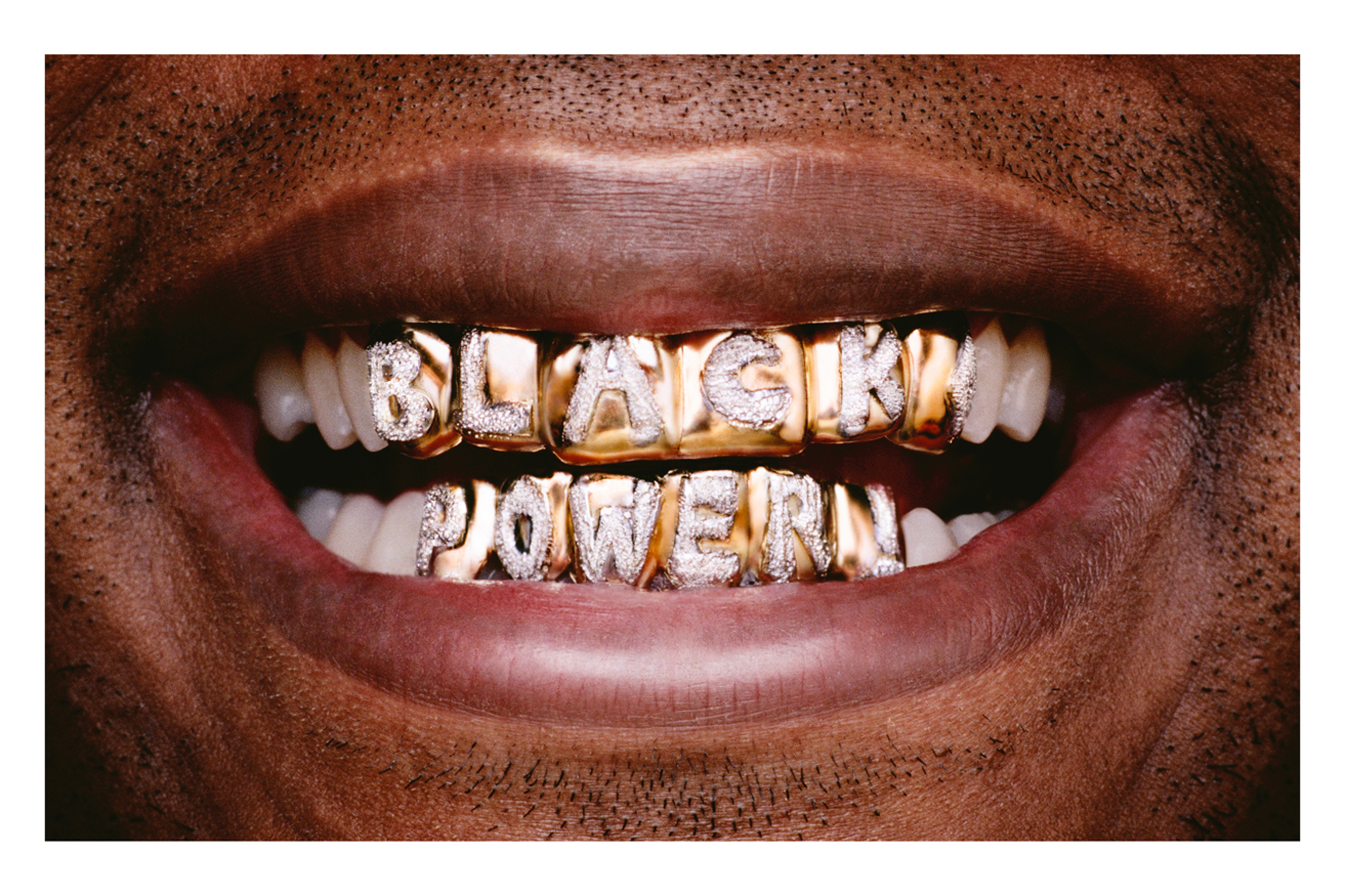

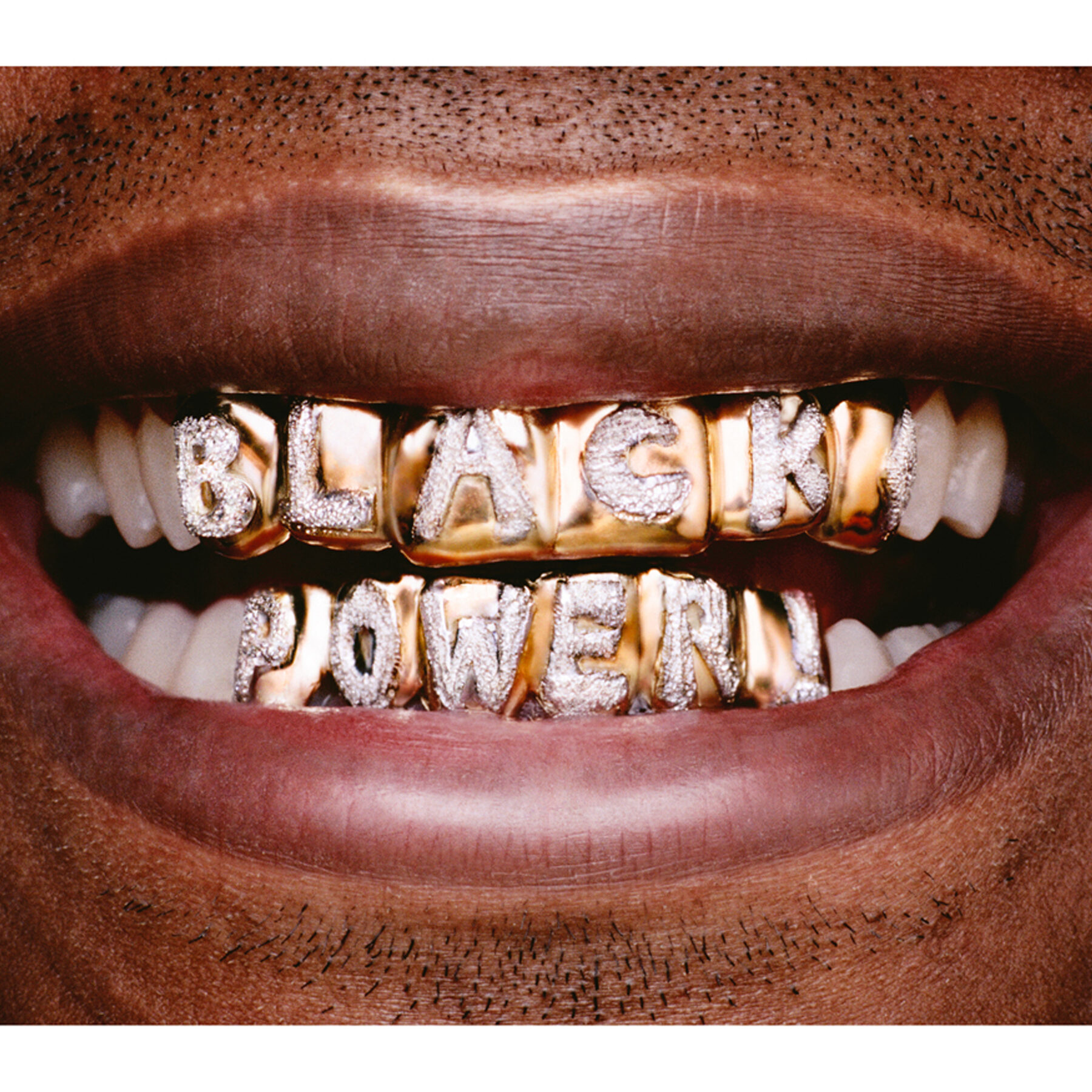

The Culture explores all the reasons hip-hop culture has endured through a showcase of modern artwork from around the world. Showstoppers include Dionne Alexander’s recreation of rapper Lil’ Kim’s iconic Versace and Chanel wigs from the early 2000s, and massive Air Force 1s—a staple in streetwear—constructed from reused car parts by artist Aaron Flowers. A haunting offering by Deana Lawson shows a photograph of young Black men draped in gold next to George Washington’s dentures, which were partially composed of teeth from the enslaved, reminding observers of the inextricable loss that still haunts African American culture.

Initially curated by teams in Baltimore and St. Louis, including Hannah Klemm, the former associate curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Saint Louis Art Museum, the Toronto presentation of The Culture is equipped with Canadian hip-hop touchstones. Drake’s puffy red Moncler jacket from the “Hotline Bling” video, a black and white portrait of local artist Kalmplex, shot by Zanele Muholi, and other local lore abound, curated by Julie Crooks, the AGO’s curator of arts of global Africa and the diaspora. Below, Crooks and Klemm share their experiences working on the show, building community consensus on its contents and building trust with local and international artists.

Something unique about this exhibit is that it was put together by a team of curators from different museums in different cities. How did the collaboration between the different museums come to be, and what was the impetus behind doing an exhibit on this subject matter in particular?

Hannah Klemm: We started from a place of terror, but I mean that positively! Hip-hop is very treasured by people and very protected by listeners, by artists, by DJs and by every facet of the community. Its origin stories are mythic and argued at every turn. So we thought, how do we approach this from our expertise—as contemporary art people, community organizers and educators—in a way where we can create something that is open-ended and allows communities to have a voice?

The [now] director of the Baltimore Museum of Art, Asma Naeem, and their [then] head of education, Gamynne Guillotte, noticed that while there had been really wonderful shows dealing with hip-hop in recent years, [they] hadn’t been as fully articulated as they thought was possible. So they started approaching institutions about creating a show that asked, “How does hip hop and contemporary art coexist? How are they influencing each other? How is one changing the landscape of the other?” Then my co co-curator Andréa Purnell and I joined on.

At first, we thought, “Are we going to get in trouble for this? Is this going to be okay?” But the way you make something like this okay is by talking to everybody. And that’s what we did. We talked to every artist in the show. We tried to talk to every curator who had ever curated a show about hip-hop. We had advisory committees. We tried to have a representative sampling of people who are invested in hip-hop, contemporary art and fashion.

Julie Crooks: We [at the AGO] were very intrigued by a show that’s interested in contemporary art through the lens of hip-hop, and we also thought it would be an exhibition that would have huge public appeal. Toronto has its own deeply rich, interesting and complex history [as it relates to hip-hop]; it also has great contemporary artists.

I was surprised to see a Telfar bag and tracksuit in the section of the show that explored the theme of hip-hop and branding, where you unpack major brand deals, but also how artists have managed to use social media to further their personal brands within the genre. Seeing something on display that many of us have in our closets begs the question of how we define what contemporary art is. What definition did you use when you were selecting what would go into the show?

JC: The full name of the show is The Culture: Contemporary Art in the 21st Century. So there’s work from the late 1990s through the 2000s, and that is deeply contemporary. With streetwear and hip-hop, Baby Phat and [Toronto’s] Too Black Guys, which was founded in the 90s—if you were wearing those [at the time], you were very contemporary.

HK: We wanted contemporary art to be genuinely of this moment. We have a lot of younger artists in the show, and emerging artists who are really exploring hip-hop from a place of a lot of access [thanks to technology] compared to having to find a mixtape on the street. They have a lot of information. While they’re young, they’re also incredibly well-versed in the field of hip-hop, and have a lot of depth of knowledge.

Are there any artists in particular that you were excited to work with?

HK: Texas Isaiah, who did the altar and photograph of rapper Ms. Boogie [in the section of the show called “Tribute,” showcasing hip-hop’s history of honouring community members both living and dead] is amazing. Their perspective, and their highlighting and uplifting of trans life within broader pop culture, is important.

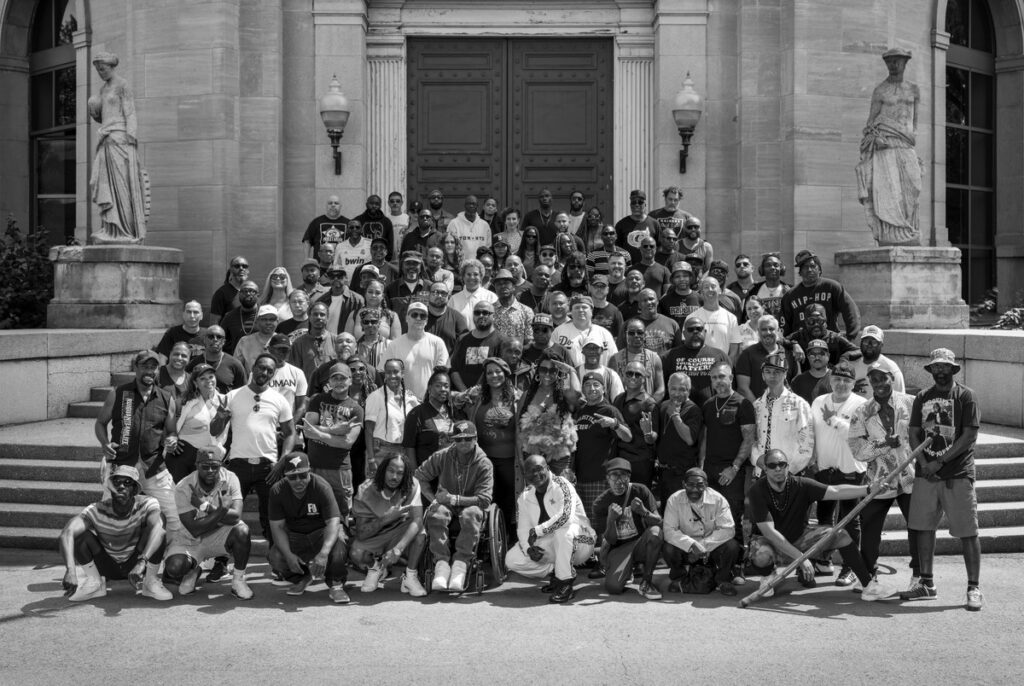

JC: Photographer Patrick Nichols has had a long relationship with many important figures in Toronto hip-hop. The beautiful portrait of a young Michie Mee was taken by him. She’s literally beaming. She’s an emcee and she’s very active on stage. Yet in this portrait, it’s a quiet moment and she seems so comfortable with the process because she knows Patrick. So there’s that level of trust that is evident in the final product. And of course, the final photograph which is this large group portrait, this historical trajectory [of Toronto hip-hop]. All of “the culture” came together and gathered for that photograph.

Get the

Three from 3

newsletter

Join our global community of sharp, curious thinkers to receive a carefully curated email of the three most important things to read, see and do this week.

Listen and learn.

Tune into Third Culture Leaders, a podcast hosted by our co-founder and publisher, Muraly Srinarayanathas.

Explore how leaders skillfully navigate multiple cultural landscapes, leveraging their diverse backgrounds to drive innovation and change.

In this show about hip-hop, you had art with Japanese influence by Los Angeles painter Gajin Fujita. There’s also a piece that’s a video of a woman in Ghana having her hair braided, and it was shot by German-born, Baltimore-based artist Yvonne Osei. These facts alone prove the thesis that hip-hop is one of the defining, transnational cultural influences of the 21st century. Yet, there are so many artforms come and go without ever leaving the neighbourhoods they were born in. What is it about hip-hop that makes it speak to so many artists from so many different parts of the world?

JC: You can appreciate jazz, but there isn’t necessarily a jazz culture. There’s small talk between people who enjoy jazz, which is also a fairly new genre, but there isn’t jazz street-wear, for example. I think that [hip-hop has] become a phenomenon because it’s not only [rap], but as the show is titled, it’s a culture. It’s this all-encompassing culture that you kind of live and breathe—it’s this larger thing.

HK: Hip-hop just speaks to such an essential form of being, and being within displacement and migration… it had a global origin story in a sense and came out of a very multicultural Bronx, with [further] origins within Jamaica, within dub music. That becomes global very quickly. Fujita’s parents are from Japan. He was a Japanese-American kid, and he ran with a graffiti group in Boyle Heights of primarily Latine youth. So again, you start to find these ways in which several different cultures are starting to bleed together through forms of gentrification, and through other kinds of systems; people find each other.

The Culture: Hip-Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century is on now at the AGO, until early April.