When the Turkish government gave amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann permission to dig up a coastal section of what is now the Biga Peninsula in northwest Anatolia in 1878, they couldn’t have imagined that Schliemann would smuggle some of the most valuable artifacts unearthed there back to his home country of Germany. Among these pieces was a set of gold jewellery that Schliemann’s wife would don to have her portrait taken—portraits that, long before the advent of social media, made their way back to Turkey and alerted authorities of the theft.

This, of course, isn’t archaeology—it’s looting. The artifacts, known collectively as Priam’s Treasure because of their (inaccurate) link to Homer’s Trojan king, mostly ended up on display in Berlin’s Royal Museums—only to be looted once again from their hiding place beneath the Berlin Zoo during World War II. Today they’re on display in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, and replicas sit behind glass in Berlin’s Neues Museum. Germany has requested that the pieces be returned to Berlin, but Russia believes they should keep them as restitution for the war. Turkey, meanwhile, is left out of the conversation completely.

The looting of art and artifacts has a history stretching back all the way to the Old Testament. Rome was sacked many times for its treasures. Looting was legalized during the American Civil War as part of their armed forces code of conduct. The British used retaliation for a small-scale attack as an excuse to take what they wanted from Benin City, Nigeria, in 1897. And the Nazis institutionalized art theft, looting thousands of works for a planned Führer Museum in Linz, Austria. At the end of that war, much of Germany’s cache of looted cultural property was reappropriated by the Americans, the British and the Russians—instead of being returned to the original owners.

As a subject matter, looting has long occupied the minds of storytellers—from Werner Herzog’s cautionary tale Aguirre, the Wrath of God to Indiana Jones’s adventures in grave robbing, to films inspired by real-world looting like The Monuments Men. More recently, The Spoils, a 2024 film from documentarian Jamie Kastner examines the legal battles undertaken by Montreal’s Max Stern Art Restitution Project. Operating out of Concordia University, the project aims to negotiate the case-by-case return of art stolen or sold from Stern’s gallery in Düsseldorf under duress in Nazi-era Germany.

“They have become,” says Kastner, “the most successful restitution effort in the world in terms of the number of cases.” Art dealer Max Stern, he explains, did not have an heir, so the film looks at restitution in a unique way. The foundation, Kastner says, is “dealing strictly with legal and moral issues, and their M.O. is to plow the proceeds from their successful claims back into the project and thus remain perpetual plaintiffs to keep this issue alive.”

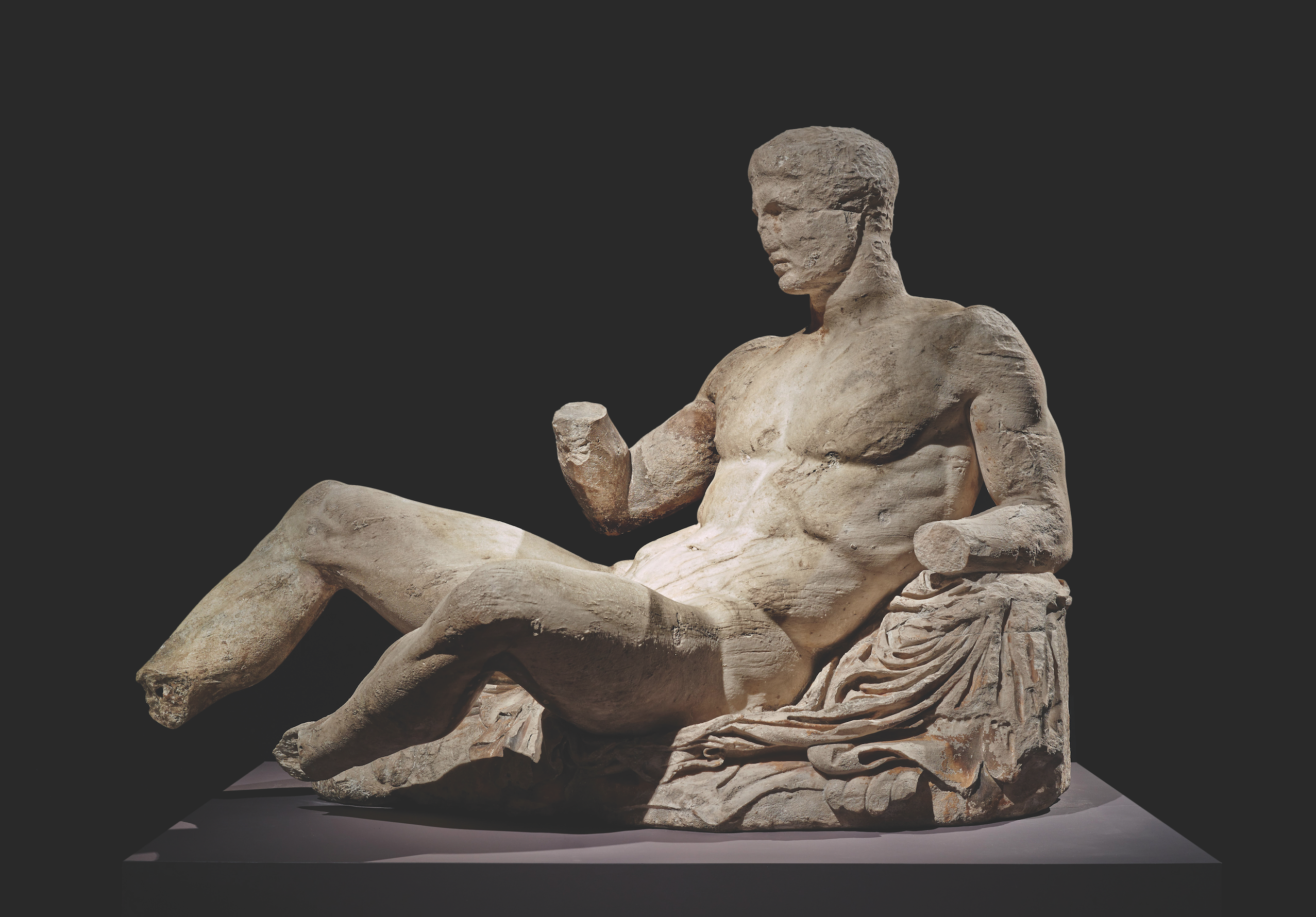

The Spoils zeroes in on a relatively recent cultural shift; today, in sharp contrast to the approach they took for much of their history, museums and galleries are responding to long-standing demands for the return of cultural property, or, at least, these institutions are less inclined to outright ignore these demands. The Greek government maintains that London’s British Museum must repatriate its collection of Parthenon Marbles, which hail from Athens in 5th century BC. The consistent pressure coming out of Greece (and reported on in international media outlets) has meant that the last two U.K. prime ministers and one deputy prime minister have had to address the issue publicly. No agreement for repatriation or for long-term loans (another solution that’s often floated in lieu of full repatriation) has been reached, however.

Perhaps due to a more dynamic, flexible approach, activist communities have found greater success in navigating the various hurdles blocking repatriation. In 2023, Heather Stevens, manager of the Millbrook Cultural and Heritage Centre in Truro, Nova Scotia, brought home a set of hand-embroidered Mi’kmaw regalia that had spent at least 135 years on the other side of the world. The repatriation was a result of years of Stevens’s conversations with an Indigenous museum colleague in Melbourne, Australia, and painstaking negotiations with the Nova Scotia government.

Museums, the way we understand them in North America, were built to be open windows on cultures and various periods in world history”

Stéphane Aquin, director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Art

Although it’s impossible to pin the uptick in the movement toward repatriation on any one factor, comments made in 2017 by French President Emmanual Macron about the outsized cache of African cultural heritage held by institutions in France are thought to be one driving factor. Following a speech in Burkina Faso that focused heavily on the issue, Macron tweeted that “African heritage cannot be a prisoner of European museums.” The message appeared to resonate with other European countries, including Germany, which subsequently decided to send more than 1,000 Benin Bronzes back to Nigeria.

In response to ongoing repatriation requests, major museums and galleries have increased efforts that at least appear to be solution-oriented: The British Museum has an online record of the contested objects contained in their collection, offering a degree of transparency into their colonial curatory past, if not repatriation and restitution.

One of the biggest legal hurdles for restitution in the case of art taken by the Nazis is the issue of duress. “I was alarmed once I started hearing some of the legalistic arguments against returning looted art,” says Kastner. “They’re tone-deaf at best. The Allied restitution law hinges on whether the painting was lost under duress, and you have all of these arguments happening after the fact about what constituted duress. It becomes inherently and deeply offensive to do this sort of litigating.”

Indeed, the laws of certain countries can act as a frustrating (and often offensive) barrier to repatriation. The 1963 British Museum Act bars the return or disposal of any item in their collection. It continues to be used as a shield to prevent the museum from returning looted items—from the more than 900 Benin Bronzes they have in their possession to the 30-plus Parthenon Marbles—to their countries of origin.

Alongside institutions like New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Paris’s Louvre, the British Museum considers itself to be one of the world’s “encyclopedic museums” whose purpose is to collect and display artifacts from across the globe and share them with an international audience. And to a degree, that view has been strengthened by the multicultural communities in which these museums exist.

“Museums, the way we understand them in North America,” says Stéphane Aquin, director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, “were built to be open windows on cultures and various periods in world history. This was done from a Western perspective. Now our communities have changed. Montreal is a multicultural, cosmopolitan city. And it’s a twist of fate to see that these museums that were based on Western assumptions and colonization of other cultures have now become relevant to people from these cultures who have made Canada their home.”

While Aquin appreciates the idea that a broad spectrum of museumgoers can visit large urban galleries and see themselves represented in their collections, he and his museum are also strong advocates for art repatriation. They, too, have Benin Bronzes in their collection—five of them. “Should we get a request for restitution, we’d study it carefully. In Nigeria, there are issues as to the exact ownership because it’s currently being contested between Nigeria and the descendants of the Oba. They’re complex questions but they’re really fascinating and we’re very active and very aware of that. We are the keepers of these works. We’re not the owners.”

Other high-profile museums and galleries lean heavily on the implication that the precious cultural artifacts they house are with them for safekeeping—that they have the budget, technology and archival practices to protect them. And yet, in 2023, the British Museum had to go public with the news that as many as 2,000 artifacts, including gemstones, gold jewellery and other precious items dating back 3,500 years, had gone missing from their archives.

“We all witnessed the irony of the British Museum saying, ‘We keep these works to protect them because we’re not sure that if we returned them, they would be safe,’” says Aquin. “And then we hear that they’re being robbed of 2,000 pieces. It certainly put a dent in their credibility.”

Get the

Three from 3

newsletter

Join our global community of sharp, curious thinkers to receive a carefully curated email of the three most important things to read, see and do this week.

Listen and learn.

Tune into Third Culture Leaders, a podcast hosted by our co-founder and publisher, Muraly Srinarayanathas.

Explore how leaders skillfully navigate multiple cultural landscapes, leveraging their diverse backgrounds to drive innovation and change.

When so many arguments against repatriation sound like excuses, the question is no longer “Why repatriation?” but “When and how?”One method is digital repatriation, practised in the extreme by Looty, a tech-driven arts collective run by Chidi Nwaubani and Ahmed Abokor. The pair’s most famous “digital heist” took place in March 2023 at the British Museum, where they showed up in matching plaid goalie masks to (completely legally) make 3-D scans of the Rosetta Stone, which they converted to NFTs that they digitally repatriated to their original home in Rashid, Egypt.

Stevens also sees activism and community-driven action as a more effective tool than government-led change. “It’s a slow roll with the Canadian government when it comes to repatriation. They find other things to be of more value than to allow us to reconnect with our culture. We are the ones that have to spearhead whatever it is that we’re doing.” For her, something that’s too often overlooked is the value and meaning these objects hold outside of the formal art and museum world.

“Everybody needs to have a part of their history,” she says. “It’s meaningful because it was made by your ancestors and it shows the work and love that they put into it.”

Looted artifacts still sit in museum collections, including: